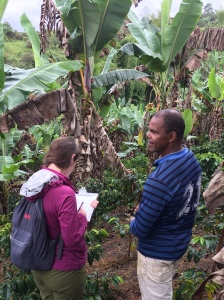

Time was ticking. This was our last full day to finalize our results before we made our final presentation to the FCC the following afternoon. We had finished visiting 16 farmers over the past 10 days collected pages of interview notes and created a vast spreadsheet to organize and analyze our findings. But one thing remained, empty cell after empty cell of missing soil analyses data. From each farm we visited we collected approximately 3 soil samples that transected the farmers’ fields from the top of the slope, through the middle, to the bottom. Gathered at the FCC’s organic compost making facility, we were staring at 50 sheets of paper holding sieved (to remove rocks and non-decomposed debris) soil air drying in preparation for their examination.

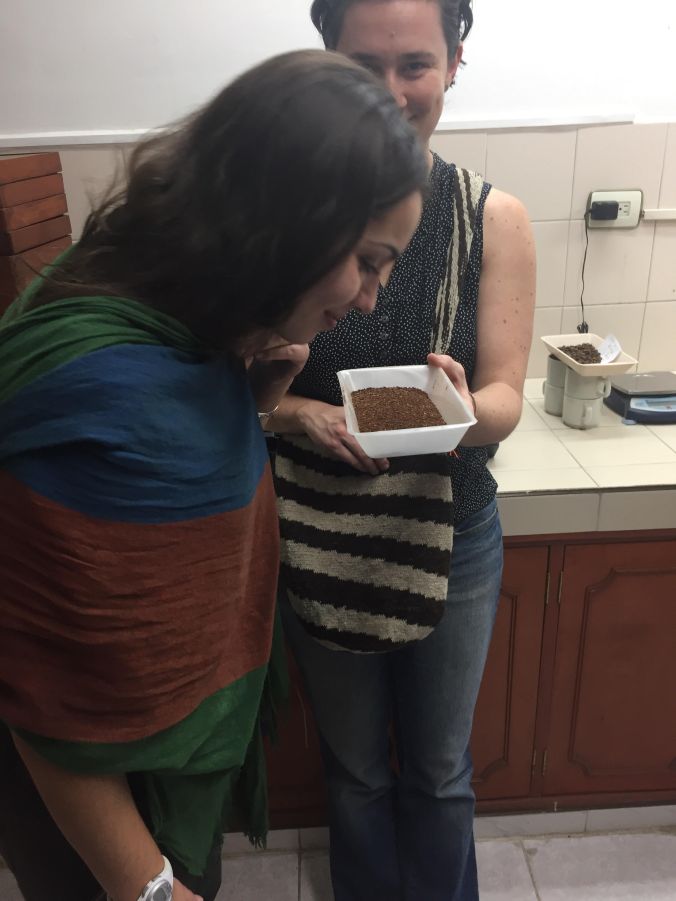

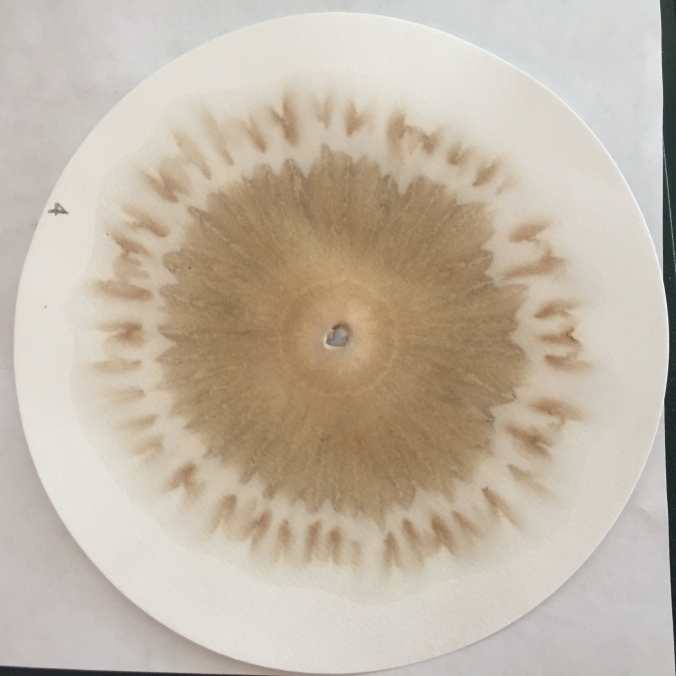

However, Arlen, the FCC field technician, wanted to round out our intercultural exchange by sharing with us a very intriguing method he uses for soil analyses, called Pfeiffer Chromatography. Developed in the 1950s, Pfeiffer Chromatography uses large filter paper impregnated with dilute silver nitrate to basically create photographic paper. A sample of soil is mixed with dilute sodium hydroxide and that solution, when applied to the filter paper via capillary action, creates a stunning image of the soil. Through understanding the the color, form, and patterns of the results, it’s theorized to give information about the quantity, quality, and interaction of the soil’s 3 Ms: minerales , materia organica, and microorganismos

One of the goals of our working with the FCC is to develop a soil analysis “kit” that is rapid, affordable, and can done with relatively simple means. This would help farmers keep tabs on soil health in the hopes that could help with making decisions about the application or purchase of soil amendments, as well as give them an idea of how their management is affecting their soils. In our first rendition of this test the parameters we measured included:

- color

- texture

- pH

- presence of earthworms

- Active Carbon

Perhaps in the future we can corroborate our customized soil health kit with the corresponding Pfeiffer Chromatography to create a hybrid quantitative/qualitative test.

Though the Active Carbon tests was originally designed to be conducted in the field as well as a lab, without precision scales, micro pipettors, and volume-setting pumps, running the Active Carbon test outside of a laboratory proved to be trickier than initially imagined, but not insurmountable! Due to technical difficulties we had to leave the factory and conduct the Active Carbon test in the kitchen of our hotel in the wee hours of the night!

But without struggle there is no triumph, and so we ended up delivering a successful presentation highlighting out preliminary findings. Reinstating our promise to continue our data analysis and to share our final results, the FCC was genuinely pleased with our work so far and has welcomed us to return to continue to develop this investigatory partnership

Thanks to the FCC who welcomed us in; thanks to Don Arlen who gave us a window to another way of thinking; thanks to the 16 farmers who hosted us, answered our endless questions, let us eat their coffee berries, and fed us excessively; thanks to Cornell’s CIIFAD program for providing the funding and opportunity!

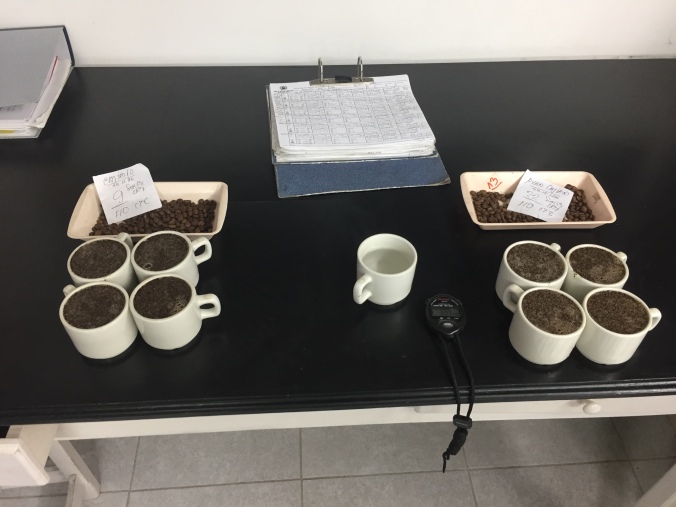

Indeed, the highest rating yet has been a 88 points! We enjoyed the taste testing and learning more about the coffee making process.

Indeed, the highest rating yet has been a 88 points! We enjoyed the taste testing and learning more about the coffee making process.